"Visistations" from the Turquoise Bear

Trules Has Supernatural "Visitations" from Famous Guests of the Historical Inn of the Turquoise Bear

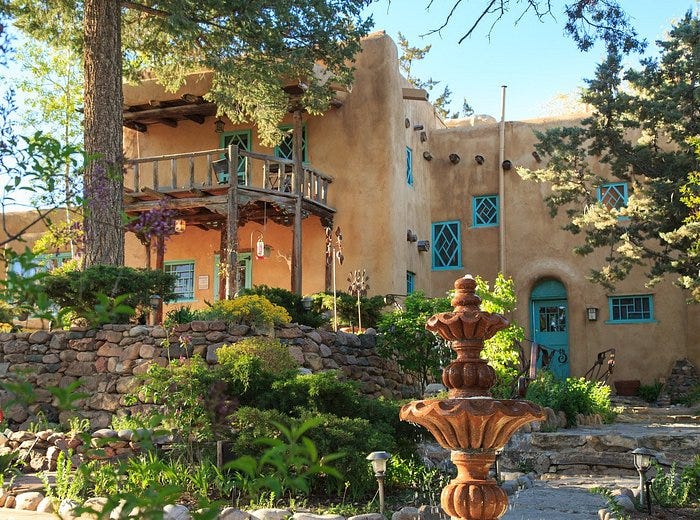

On an old rustic unpaved road, East Buena Vista Street, right near the New Mexico State Capital Building in downtown Santa Fe, sits the iconic and historic Inn of the Turquoise Bear, originally built as a small collection of adobe buildings in 1886, which for a storied period in its cherished past became the au courant homestay of some of the most famous guests ever to visit “The City Different”.

The current, beautifully restored Inn occupies the former home of Witter Bynner (1881-1968), who for almost 50 years was a prominent citizen of Santa Fe, actively participating in the city’s cultural, artistic, and political life. Noted as a poet, translator, and essayist, Bynner was a staunch advocate of human rights, especially of women, Native Americans, and other New Mexican minorities. He created his rambling adobe villa, constructed in Spanish-Pueblo Revival style, from a core of rooms that date to the 19th century, and The Inn is now considered one of Santa Fe’s most important historical estates.

With its signature portico, towering pine trees, magnificent rock terraces, and lush gardens filled with lilacs, wild roses, and other native flowers, the Inn offers guests a bucolic retreat not far from Santa Fe’s Central Plaza. Bynner and Robert Hunt, his companion of almost 40 years, were famous – or infamous – for the riotous parties they hosted on this estate, referred to by Ansel Adams as ‘Bynner’s bashes.’ Their home was regarded as the center for the creative and fun-loving elite of Santa Fe and for visitors from New York and around the world.

One day recently, during the winter off-season, on the recommendation of my childhood, and still my best friend, Rick Reaper, my wife, Surya, and I decide to stop by the Inn for “a little tour”. Of course, quite lamely, we don’t call ahead, so the concierge does the best she can, showing us the grounds and the communal dining room, telling us some of the “infamous history”, while also informing us,

I’m sorry but I’m afraid I can’t show you any of the rooms themselves today because they’re not made up. It’s off-season as you know, and we weren’t expecting any guests other than the ones we already have in the ‘Willa Cather Room’.

I understand, I say, I should have given you a call. I will in a couple of days and we’ll come back to see the rooms.

Excellent. Please do.

We leave, a little disappointed. (I should speak for myself.) But hey, “The Willa Cather Room”? I’m reading her most famous book right now, her 1927 novel, “Death Comes for the Archbishop”, a fictionalized story based on two historical figures of the late 19th century, Jean-Baptiste Lamy, Santa Fe’s renowned Catholic bishop, and Joseph Projectus Machebeuf, his friend and fellow priest, about their attempts to establish a new diocese in the New Mexico Territory, long before its Statehood in 1912.

Bishop Lamy is the namesake of Santa Fe’s well-known “Bishop’s Lodge”, the one-time home of the ambitious bishop, now another beautifully restored tourist inn and restaurant, not far up the mountain from the U.S. Army’s 19th century-built Fort Marcy, the only remaining fort from the Mexican-American War (1846-48).

Cather’s novel is often ranked as one of the best of the 20th century, and it is outstanding for its poetic description of New Mexico’s people and landscapes. One such description speaks directly to me, as it resonates with the people of my own Tribe.

These Acoma Indians, born in fear and dying by violence for generations, had at last taken this leap away from the earth, and on that Rock had found the hope of all suffering and tormented creatures—safety. They came down to the plain to hunt and to grow their crops, but there was always a place to go back to. If a band of Navajos were on the Ácoma’s trail, there was still one hope; if he could reach his rock—Sanctuary! On the winding stone stairway up the cliff, a handful of men could keep off a multitude. The rock of Ácoma had never been taken by a foe but once,—by Spaniards in armour. The Rock, when one came to think of it, was the utmost expression of human need; even… the Hebrews of the Old Testament, always being carried captive into foreign lands,—their rock was their idea of God, the only thing their conquerors could not take from them.

Walking away from the Turquoise Bear, I feel a strong tug, as if it doesn’t want to let me go. As if it wants to speak to me. Tell me its secrets.

Naturally, the most downhill cottage on the edge of the property is Ms. Cather’s. Does she know I’m reading her book? What does her spirit want to tell me? I look at her photo above and… she seems to be looking right at me. She’s certainly from a different time… she was born in 1873 and died just a few months before I was born in 1947.

Like my son, Exsel, often says to me,

That was back in your century.

It’s funny, I admit, but it always sort of irks me, while, what can I say, it’s true.

She’s certainly dressed differently. She looks uncommonly - timeless. Maybe because - she’s an artist. A writer. Like many of Witter Bynner’s other “salon guests”, where the celebrity list includes D.H. Lawrence (who spent his first night in an American home in this villa), Ansel Adams, Igor Stravinsky, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Robert Frost, W.H. Auden, Aldous Huxley, Clara Bow, Errol Flynn, Rita Hayworth, Christopher Isherwood, Martha Graham, Robert Oppenheimer, Georgia O’Keeffe, Thornton Wilder, J.B. Priestly – and many others. In fact, each of the Inn's 11 rooms, is named for one of these famous past guests, and although they vary greatly in size and decor, each room captures the historic style of Santa Fe’s early 20th century - thick adobe walls, wood-beam ceilings, and pinon-burning fireplaces, with several rooms having cozy sitting areas and private porches.

But I’m wondering… what do these historic personalities want to tell me, now that I’ve moved to “The Land of Enchantment”, almost a century after they visited?

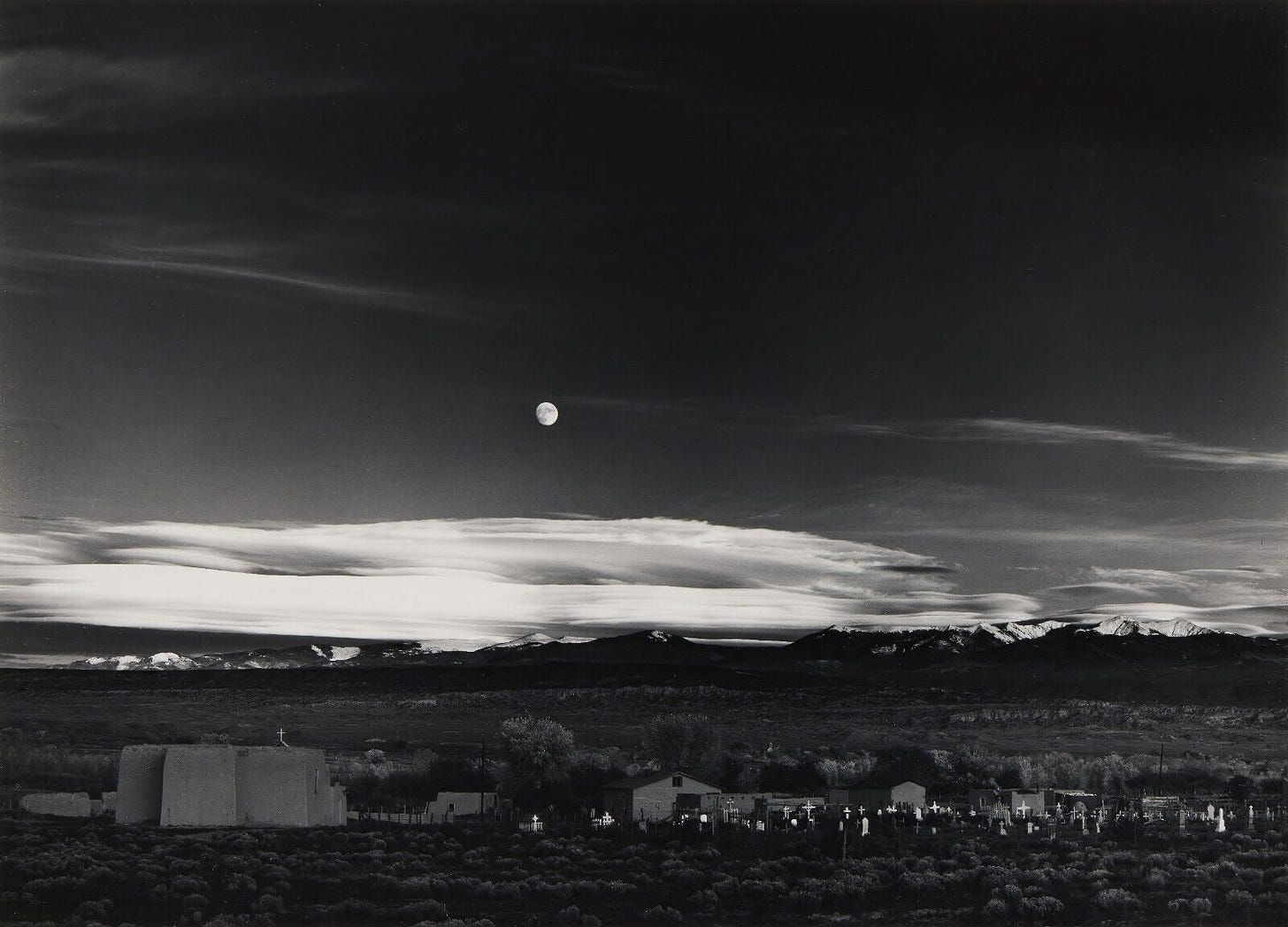

This is a young Ansel Adams (1902 -1984), important conservationist, writer, teacher, and photographer, who profoundly influenced future generations of artists, photographers, and environmentalists. There can be little doubt that he produced some of the most iconic images of the great American wilderness. He helped found Group f/64, an association of photographers advocating "pure photography” which favored sharp focus and the use of the full tonal range of a photograph, shooting pristine and gorgeous black-and-white photos of the American West.

Well, I’m certainly no Willa Cather or Ansel Adams, but… here I am, “a city boy” (having lived in New York, Chicago, and LA my whole life) now suddenly enjoying my retirement in “The American West”. Living under clear blue New Mexican sky, 7200 feet high up in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, at 75 years old, I’m first learning about the original Anasazi people who populated the arid “Southwestern” desert for millennium before the conquering and colonizing Spanish built Santa Fe’s Central Plaza in 1609. First learning at Santa Fe’s downtown New Mexico History Museum about the indigenous “Pueblo Revolt” in 1680, the transfer of Santa Fe’s government to the newly-declared nation of Mexico from the time of its independence in 1821 until “New Mexico’s annexation” by American Manifest Destiny in 1846, when General Stephen Kearny’s army marched west from Independence, Missouri, 870 miles along the Santa Fe Trail right into the Palace of the Governors on the downtown Plaza. Hell, Santa Fe was even under the command of the Confederate South for three weeks in the Spring of 1862!

But back to those voices….

I first came to Santa Fe in 1927, says Ansel Adams. This was our first trip east of the Sierra and the Cajon Pass. We wanted to see Mary Austin, Witter Bynner, and many others who embraced the Southwest spirit in Santa Fe and Taos.

. . . Wherever one goes in the Southwest one encounters magic, strength, and beauty. Myriad miracles in time and place occur; there is no end to the grandeurs and intimacies, no end to the revival of the spirit which they offer to all."

On that first trip, Adams photographed Taos Pueblo, producing the magnificent limited edition book Taos Pueblo containing twelve original prints, Gems From New Mexico. On his second trip to Taos, Adams stayed at the home of Mabel Dodge and Tony Lujan where Paul Strand (“the creator of modern American photography”) and Georgia O'Keeffe were guests.

But undoubtedly Adams's most spectacular moment in New Mexico took place in 1941. Accompanied by his eight-year-old son Michael, he was photographing national parks in California under the aegis of the Department of the Interior when he entered northern New Mexico on November 1. Near the village of Hernandez, Adams saw a spectacular scene; a full moon rising over snowcapped peaks lit by the late afternoon sun. In the distance lay a small adobe church and a cemetery filled with white crosses.

Sometimes I do think I get to places just when God is ready to have someone click the shutter!

Here is Adams’ account of making "Moonrise", which many art historians and critics consider one of the greatest photographs of the 20th century.

I was driving back to Santa Fe from the Chama Valley and I saw this wonderful scene out of the window. The reaction was so strong I practically drove off the road. I got out the tripod and camera, took the front part of the lens off, screwed it on the back of the shutter and began composing and focusing… I couldn't find my exposure meter, but I knew… the basic exposure was a twentieth of a second. I made one picture, and while I was turning the holder around and pulling out the slide to make a duplicate, the sunlight went off the crosses. I got the picture by about 15 seconds!

If I had spent more time in the Chama Valley, I would have missed the entire thing. If I had come home earlier, I would have missed it. So there's always an element of chance in photography. If you have practiced and practiced, the process is intuitive. You suddenly recognize something, and you react.

Adams came to New Mexico many times, also notably, in the autumn of 1937 when Georgia O'Keeffe invited him to visit her in Abiquiu. Adams photographed her near her home painting the landscape, where she was creating some of her most acclaimed work.

When I, personally, look at some of her New Mexico painting, most of which she did on, or near, her beloved Ghost Ranch, just a short jaunt from Santa Fe, where I went with my Indonesian family, I can almost hear her speaking - bits and pieces - of what she thought about her art.

I have things in my head that are not like what anyone has taught me - shapes and ideas so near to me - so natural to my way of being and thinking that it hasn't occurred to me to put them down.

I found I could say things with color and shapes that I couldn't say any other way - things I had no words for. I often painted fragments of things because it seemed to make my statement as well as or better than the whole could.

It was all so far away - there was quiet and an untouched feel to the country and I could work as I pleased. Nobody sees a flower really; it is so small. We haven't time, and to see takes time - like to have a friend takes time.

When you take a flower in your hand and really look at it, it's your world for the moment. I want to give that world to someone else. Most people in the city rush around so, they have no time to look at a flower. I want them to see it whether they want to or not.

One can not be an American by going about saying that one is an American. It is necessary to feel America, like America, love America and then work. The days you work are the best days. To create one's world in any of the arts takes courage.

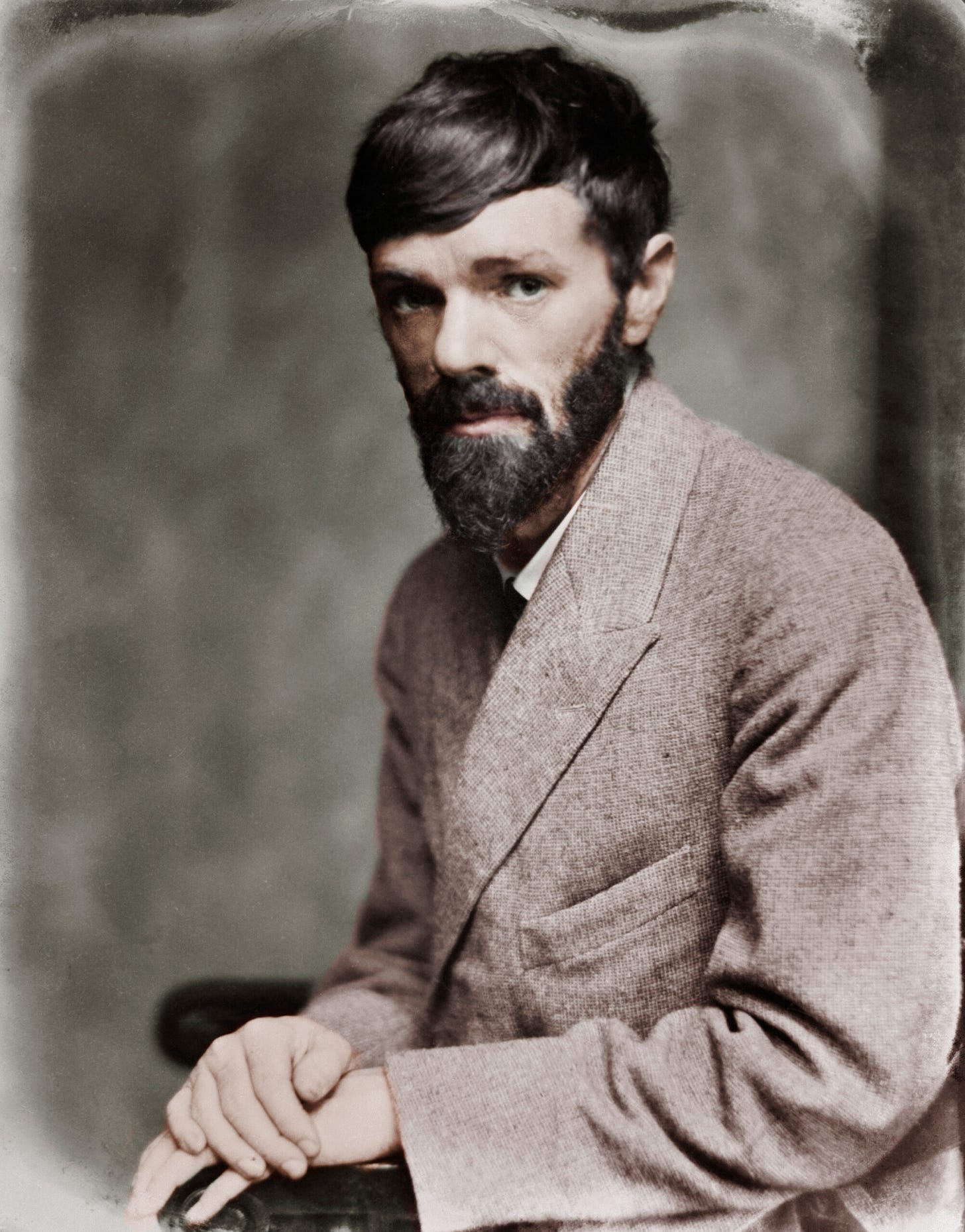

And what about D.H. Lawrence (1885 - 1930), preceding Adams and O’Keeffe, the original British “bad boy” of the modern contemporary novel? Hero of my literary heroes, Henry Miller and Lawrence Durrell. Penner of such classics as “Lady Chatterly’s Lover”, “Women in Love”, “Sons and Lovers”, and “The Rainbow”.

Over the course of three years, 1922-25, after staying with Witter Bynner on his first night in America, but eventually moving on to Taos further north (one of the first “artists” to do so),) here is what Lawrence tells me about New Mexico:

In a cold like this, the stars snap like distant coyotes, beyond the moon. And you’ll see the shadows of actual coyotes, going across the alfalfa field. And the pine trees make little noises, sudden and stealthy, as if they were walking about. And the place heaves with ghosts. But when one has gotten used to one’s own home ghosts… they are like one’s own family, but nearer than the blood. It is the ghosts one misses most, the ghosts there, of the Rocky Mountains.

In an article for the “NY Times”, Henry Shukman also tried to capture what struck Lawrence as he traveled north from Santa Fe to Taos:

There’s something about the first glimpse of the Taos Mesa as you travel north from Santa Fe, up the narrow canyon of the Rio Grande. A series of long, sweeping bends brings you over a brow, and suddenly the view ahead opens out onto empty, bare land, with a smoky gorge cut into it... Ten miles off stands a bulk of dark, brooding mountains. One of the biggest, bald Taos Mountain, sits bolted to the plain like a remonstrance. At its foot, the town of Taos spreads like litter glinting in the sun.

It would be impossible to live at the foot of that mountain for a thousand years, as the Indians of the Taos Pueblo have done, and not come to think of it as sentient — the Kong of northern New Mexico. This was, in a sense, why the painters who “colonized” the area in the early 1900’s came. As one who passed through, Maynard Dixon, put it: “You can’t argue with those desert mountains — and if you live among them enough — like the Indian does — you don’t want to. They have something for us much more real than some imported art style.

This was the creed of the American modernists who clustered in Taos in the early decades of the last century: Taos would soon become a fount of a new Americanism in art, an ever-flowing alternative to Europe. But Taos also had its appeal for Europeans too: Lawrence, Aldous Huxley, Carl Jung, and Leopold Stokowski were only a few of the European artists and thinkers who found their way there. The reason they went was because of one pioneering American woman.

It was from the foot of Taos mountain that Mabel Dodge Luhan — heiress, patroness, columnist, early proponent of psychoanalysis, “manic-depressive”, memoirist, and hostess — planned the rebirth of Western civilization. She moved to Taos from the East Coast in 1917 and fell in love not only with the place but also with Tony Lujan (later anglicized to Luhan), a chief in the nearby Pueblo. She promptly left her previous husband, married Tony, and expanded a house on the edge of town, turning it into an adobe fantasy castle (what Dennis Hopper, who owned it in the 1970s, would later call “The Mud Palace”), and began to invite scores of cultural luminaries. The idea was to expose them to the Indian culture she believed held the cure for anomic, dissociated modern humanity. After dinner, drummers and dancers from the pueblo would entertain the household.

Then again, Lawrence had his own reasons for coming to New Mexico. For years he dreamed of founding a utopian community, to be called Rananim, and he hoped to do it, perhaps, on, or near, the ranch that Mabel Dodge Luhan “bequeathed” him and his wife Frieda, the only home, Lawrence ever “owned”. He was also consumptive, and his worldwide search for a civilization answering to humanity’s spiritual needs, his “savage pilgrimage,” also included a personal search for a healthy climate. New Mexico, unlike Texas and California, welcomed tuberculosis sufferers. High, dry, clean air — just what the doctor ordered.

The ghosts there, they never go beyond the timber; I know them, they know me: we go well together.

Poets, authors, playwrights, music composers, Hollywood movie stars, painters, dancers, European intellectuals, visionaries… Aldous Huxley, they all came to Witter Bynner’s home in the 1920s and 30s.

All European avenues had been exhausted in the search for a way forward – politics, art, science – pitching everyone toward the US by 1937. Before WW2.

All looking for a “Brave New World”. Why not New Mexico, in Santa Fe and Taos?

The poetic voices and dancing duets keep coming to me over the next many days and weeks. The Blue Bear seems to have inundated my spirit. Seems to be singing to my psyche.

I can’t expand upon all these visitations in this single post. Once again Substack is telling me,

Near email length limit!

But I can say, at least with the famous dancers who stayed with Witter Bynner… I danced.

Rita Hayworth. Martha Graham….

Hey, I used to be pretty good “back in the day”. “A professional”. Not only a “modern dancer”, but I could hold my own at Roseland Ballroom when it was on 8th Avenue and West 52nd in New York City, as well as at Studio 54 in the late 70s, when they used to swing open the red velvet ropes for me and all my friends (well, at least for Gino Cumeezi, my clown alter ego, and all his friends!)

Of course, I accommodate my style for each of the great dance divas. With Rita, in her form-fitting, sexy decolletage ballroom gown, I have one arm of my brown and white, double-breasted pinstripe suit buried deep around her waist, when not extended for a partnered twirl,

while with Ms. Graham, I’m barefoot, in black leotard shorts, doing convulsive abdomen contractions, never getting closer than three feet from her terrifying personage.

With Errol Flynn, I remind him of the time I swam with him in Boston Bay, Jamaica, where he owned a home to get away from the Hollywood rumor mill he always hated, being told he “couldn’t act”, and that he should “keep to swashbuckling pirate roles and fancy swordplay”. No wonder he drank on set, became a womanizer and hedonist, and died so young, barely 50 years old. I remind him, too, that at least, he did spend a few glorious days in sun-baked, rustic Santa Fe, and that I, in any event… remember him well and… fondly.

Upon Witter Bynner’s death in 1968, he willed the estate to St. John’s College in Santa Fe which used the grounds as residence halls for many years. In 1996, Ralph Bolton & Robert Frost (not the poet), purchased the estate and created the present-day Santa Fe bed and breakfast, Inn of the Turquoise Bear. They faithfully restored the original property, which is now on the National Register of Historic Places. Since then, the estate hasn’t been altered in any significant way, retaining its authentic Northern New Mexico architecture and charm. In April 2014, Dan Clark & David Solem acquired the Inn. Their goals, as innkeepers and stewards of the estate and land that Bynner loved are:

to rekindle the comfort, creativity, and hospitality for which the home was renowned, to protect, restore and extend the legacy of its famous creator, and to provide their guests with a unique, restorative experience that captures the essence of Santa Fe’s past and present.

And what a leagcy it is! What a list of artists and thinkers! Right down the street here in downtown Santa Fe.

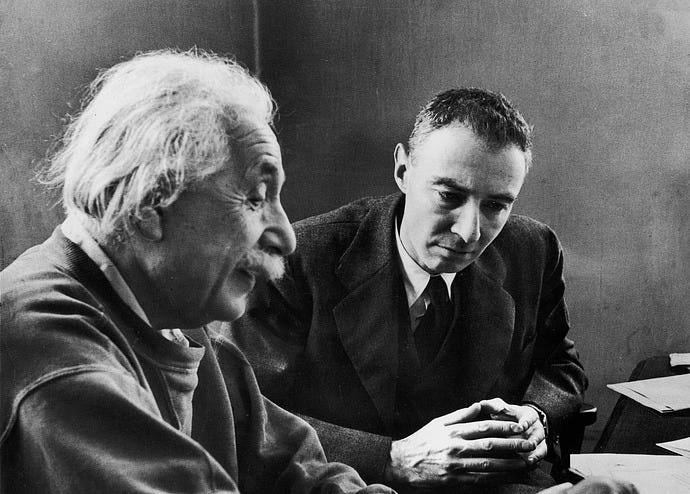

I wonder if J. Robert Oppenheimer was one of Bynner’s last famous guests while he was working so feverishly on developing the atomic bomb (1943-45), just a stone’s throw away in Los Alamos, New Mexico. If so, I like to think that the beauty and charm of Bynner’s home was a comfort to him and his family. Maybe even his friend, Albert, met him there for some schnaps?

But then again, I can’t say that I noticed the Inn of the Turquoise Bear in the recent Oppenheimer movie. Did you?

Finally, I’d like to leave you with the words of Mr. Frost (yes, that one, Robert, the poet, who also stayed with Witter Bynner on East Buena Vista Street), whose singular poem I have been familiar with long before I moved to New Mexico and became a retired Southwesterner…

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel to both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

If you enjoyed this post, or any previous ones, please LIKE IT (by clicking the Heart), and LEAVE A COMMENT. It continues to help build an enthusiastic and interactive readership.

Also, if you have any friends who you think might enjoy Santa Fe Substack, PLEASE SHARE IT WITH THEM.

ALSO, a REMINDER, to CHECK OUT “TRULES RULES on SUBSTACK” with over 100 posts and re-posts of “rants, raves, reports, and points of view + top-rated travel podcasts and some common sense”.

Thanks so much!!!

—

Visit “Trules Rules” on Substack HERE

Visit my personal blog “Trules Rules” HERE

Travel the world with my “e-travels with e. trules” blog

Listen to my travel PODCAST HERE

Or go to my HOMEPAGE

My Twitter (X) handle: @etrules

This is my favorite yet, love how your digging into Santa Fe and leading the way, so very glad we met you!

Beautifully visually written (as per usual), and so enlightening...